On June 4, Hong Kong lawmakers approved retired New Zealand judge William Young to sit as a non-permanent overseas judge on the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal. Young’s appointment reversed a trend of foreign judges departing Hong Kong’s top court, prompting Mark Clifford, president of the Committee for Freedom in Hong Kong Foundation, to write the following opinion piece, first published in New Zealand’s The Post in a slightly edited format.

China promised the people of Hong Kong that their freedoms would continue when it took over the British colony in 1997. Gradually and then aggressively, it has gone back on its word. Now a distinguished New Zealander is helping the regime get away with it.

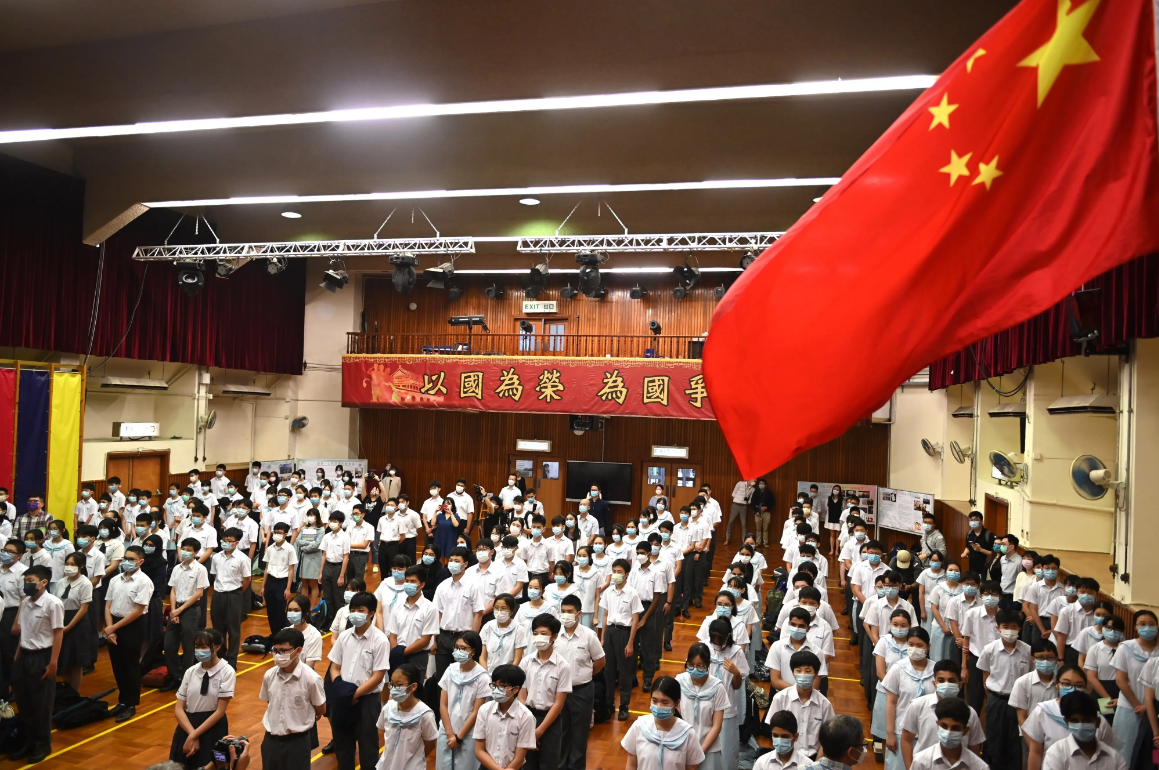

Once one of Asia’s freest places, Hong Kong is now a dangerous place to disagree in any way with the Chinese Communist Party. A vague and sweeping National Security Law imposed five years ago has criminalized dissent. Today, the city holds more than 800 political prisoners behind bars. Hong Kongers have been jailed for wearing a T-shirt that the authorities don’t like and for refusing to stand respectfully enough for the national anthem.

Government and human rights organizations around the world have condemned what is arguably the fastest and most sweeping destruction of an open society in living memory. Reporters Without Borders ranks Hong Kong near the bottom of its press freedom list at number 140, plummeting from 18 when the list started in 2003. “We have never seen such a sharp and rapid deterioration in the press freedom record of any country or territory,” said Aleksandra Bielakowska of Reporters Without Borders.

Countries have protested by withholding support. The United States has imposed sanctions on senior Hong Kong officials, including chief executive John Lee. Six foreign judges have quit their jobs with Hong Kong’s Court of Final Appeal, the territory’s top court, since the beginning of last year. From a high of 15 foreign judges, only five foreigners sat on the court at the end of May.[i] In 2022, the UK government ended the agreement allowing sitting British judges to serve on the court.[ii]

Why, then, has a former top judge from New Zealand decided to join that court? On June 4, Hong Kong’s Legislative Council approved Judge William Young, who retired as a permanent judge from the Supreme Court of New Zealand in 2022 after 12 years of service, to join the Court of Final Appeal. Young also led the Royal Commission Inquiry into the Christchurch terror attack.

It is Young’s fifth international judicial appointment. In 2022 he was appointed an ad-hoc justice in the Court of Appeal of the Seychelles and a judge of the Court of Appeal of Samoa. In 2023, he was sworn in to the Supreme Court of Fiji. He was also appointed a judge of the Dubai International Financial Centre Courts in July 2022, but resigned less than a month later after human rights campaigners raised concerns that foreign judges were being used to legitimize the United Arab Emirates political regime.

As was the case in Dubai, Hong Kong’s appointment of Young brings a veneer of credibility to its legal system. The appointment of foreign judges might help convince sceptics that its common-law tradition, developed during 156 years of British colonialism, remains robust. Hong Kong Chief Executive John Lee called Young a “judge of eminent standing” who would contribute greatly to Hong Kong’s top court and demonstrate its independence.

Young’s decision to join the Hong Kong court is even more curious because of his quick resignation from the Dubai court. He hasn’t been willing so far to discuss why this decision is not, like that one, complicated by questions of judicial independence that have prompted others to quit. He told the Post that “I would not accept appointment to that Court unless satisfied that it was proper for me do so.”

Foreign judges generally sit on the bench for one month at a time, with remuneration of about US$50,000 per session, as well as accommodation and flights. In the last few years, five British judges have stepped down from Hong Kong’s court. When Lord Reed quit in 2022, he issued a statement that British judges “cannot continue to sit in Hong Kong without appearing to endorse an administration which has departed from values of political freedom, and freedom of expression.”[iii]

Jonathan Sumption, one of Britain’s most distinguished jurists, resigned from the Court of Final Appeal a year ago.[iv] Lord Sumption called the politically motivated prosecutions of journalists and opposition figures “milestones on the road to totalitarianism in a territory once notable for its political diversity.” They are, he added, “difficult to reconcile with the rule of law.”[v]

In Hong Kong, the National Security Law has done away with trial by jury, replacing it with a panel of hand-picked judges: a violation of a promise China made in the city’s mini constitution. Defendants are typically denied bail, again despite constitutional promises that bail arrangements would remain unchanged from the British period. Ironically, foreign barristers, long a feature of Hong Kong’s legal scene, are denied in National Security Law cases. Foreign judges are fine but lawyers acting for the defense are not.

It’s a disgrace that Judge Young is letting himself be used by such a repressive government after his long and distinguished service in New Zealand. He should resign before the country is tainted by his participation.

Mark L. Clifford is the president of the Committee for Freedom in Hong Kong Foundation. He holds a PhD in Hong Kong history and is the author, most recently, of The Troublemaker: How Jimmy Lai Became a Billionaire, Hong Kong’s Greatest Dissident and China’s Most Feared Critic.

Picture credit: The Post

[i] https://hongkongfp.com/2025/06/05/hong-kong-lawmakers-endorse-new-zealand-judge-for-top-court/

[ii] Sumption (see below), p. 77.

[iii] Ibid., p. 77.

[iv] Jonathan Sumption quotes are from his book The Challenges of Democracy, London: Profile Books, 2025, notably the chapter Hong Kong: A Modern Tragedy, pp. 50-80. Sumption page 60 describes working of the court (4 permanent judges and one non-permanent, who may be foreign).

[v] Ibid., 71.