This blog is authored by James Joseph, a human rights advocate and foreign policy specialist and the Founder and Director of The Duty Legacy and The Alliance for the Prevention of Atrocity Crimes.

On June 3–4, 1989, the world watched in horror as the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) unleashed a brutal military crackdown on peaceful pro-democracy protesters in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. The Tiananmen Massacre, which killed hundreds—possibly thousands—of unarmed civilians, remains one of the most defining moments of modern Chinese history. Tiananmen Square has been a site of demonstrations and protests for decades, even before the Communist Party came to power in 1949. The iconic image of “Tank Man,” (pictured below) a lone individual standing defiantly before a column of tanks, became a global symbol of courage against authoritarian oppression. Thirty-six years later, the massacre’s legacy is a stark warning of the CCP’s willingness to prioritise control over human rights—a pattern that continues in Hong Kong, Xinjiang, Tibet, Taiwan, and beyond. Yet, the world’s response, shaped by a stranglehold of economic dependence and geopolitical timidity, reveals a troubling truth: we have failed to learn from China’s overreach. As the CCP refines its repressive tactics and wields its economic might to silence criticism, the unaddressed lessons of Tiananmen cast a long shadow over global human rights advocacy.

The Tiananmen Massacre: A Turning Point

The Tiananmen protests began in April 1989, sparked by the death of Hu Yaobang, a reformist leader whose passing galvanised students, workers, and intellectuals to demand political openness, freedom of expression, press freedom, and an end to corruption. What started as a student-led movement in Tiananmen Square grew into a nationwide call for reform, with millions participating across Chinese cities. The CCP, perceiving these demands as an existential threat to its monopoly on power, declared martial law in late May. On June 3–4, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) moved into Beijing with tanks and live ammunition, opening fire on unarmed civilians. The bloodshed shocked the world, with international media capturing scenes of chaos and carnage.

The image of ‘Tank Man’ endures as a global symbol of

courage in the face of oppression. (Wikipedia Commons)

The exact death toll remains a closely guarded secret, as the CCP has suppressed all official records. Estimates range from hundreds to over 10,000, with the Tiananmen Mothers—a group of victims’ families—documenting 202 confirmed deaths in Beijing and other cities. The group, led by figures like 87-year-old Zhang Xianling, continues to face harassment and surveillance for demanding accountability. The massacre was a turning point, signalling the CCP’s unwavering commitment to authoritarian control and setting the stage for decades of repression. It also marked the beginning of China’s economic ascent, as the Party sought to restore legitimacy through prosperity while stifling political freedoms.

A Legacy of Censorship and Control

Within China, the Tiananmen Massacre is a forbidden topic, erased from public memory through relentless censorship. The CCP’s Great Firewall blocks terms like “June 4,” and images of “Tank Man” are scrubbed from the internet. Schools do not teach the event, ensuring that younger generations remain largely ignorant of it. Recent examples underscore this erasure: in November 2024, a Hong Kong lamppost coded FA8964—a subtle nod to June 4, 1989—was relabelled to avoid reference to the massacre. In December 2024, Cathay Pacific issued an apology for Tiananmen-related content, illustrating the pervasive reach of self-censorship. The CCP’s use of advanced surveillance—facial recognition, social credit systems, and real-name social media registration—ensures that dissent is swiftly detected and suppressed.

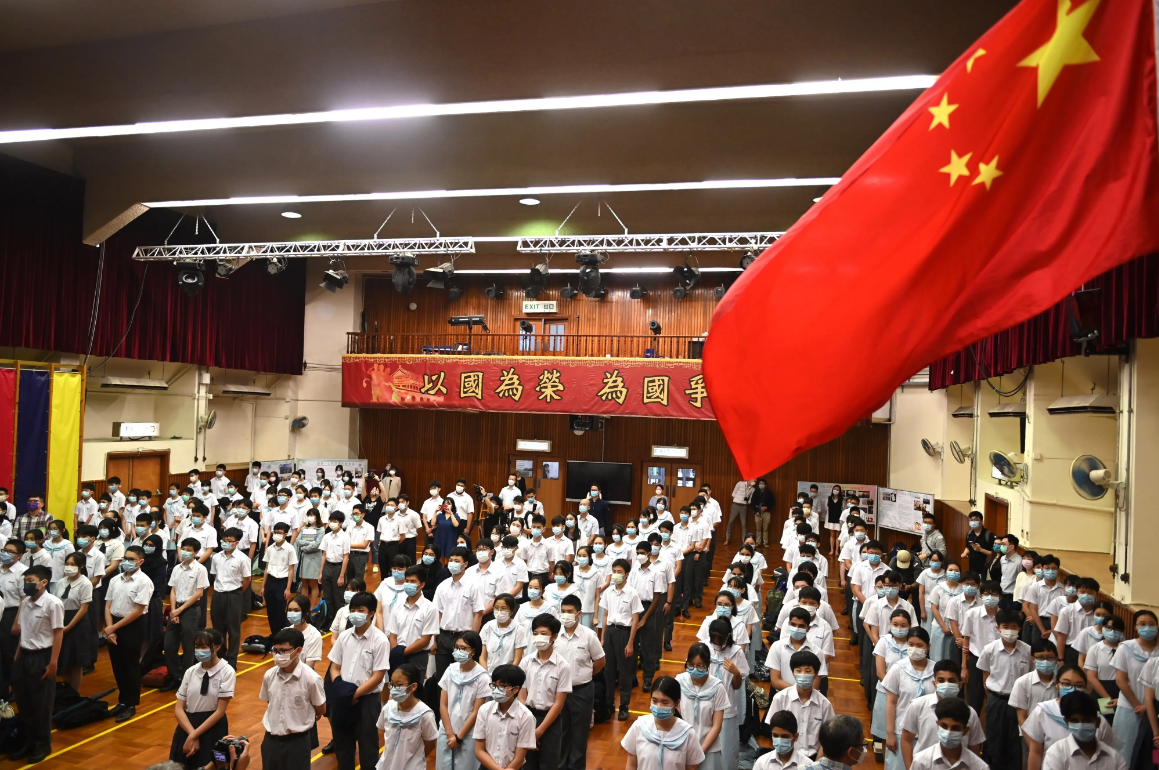

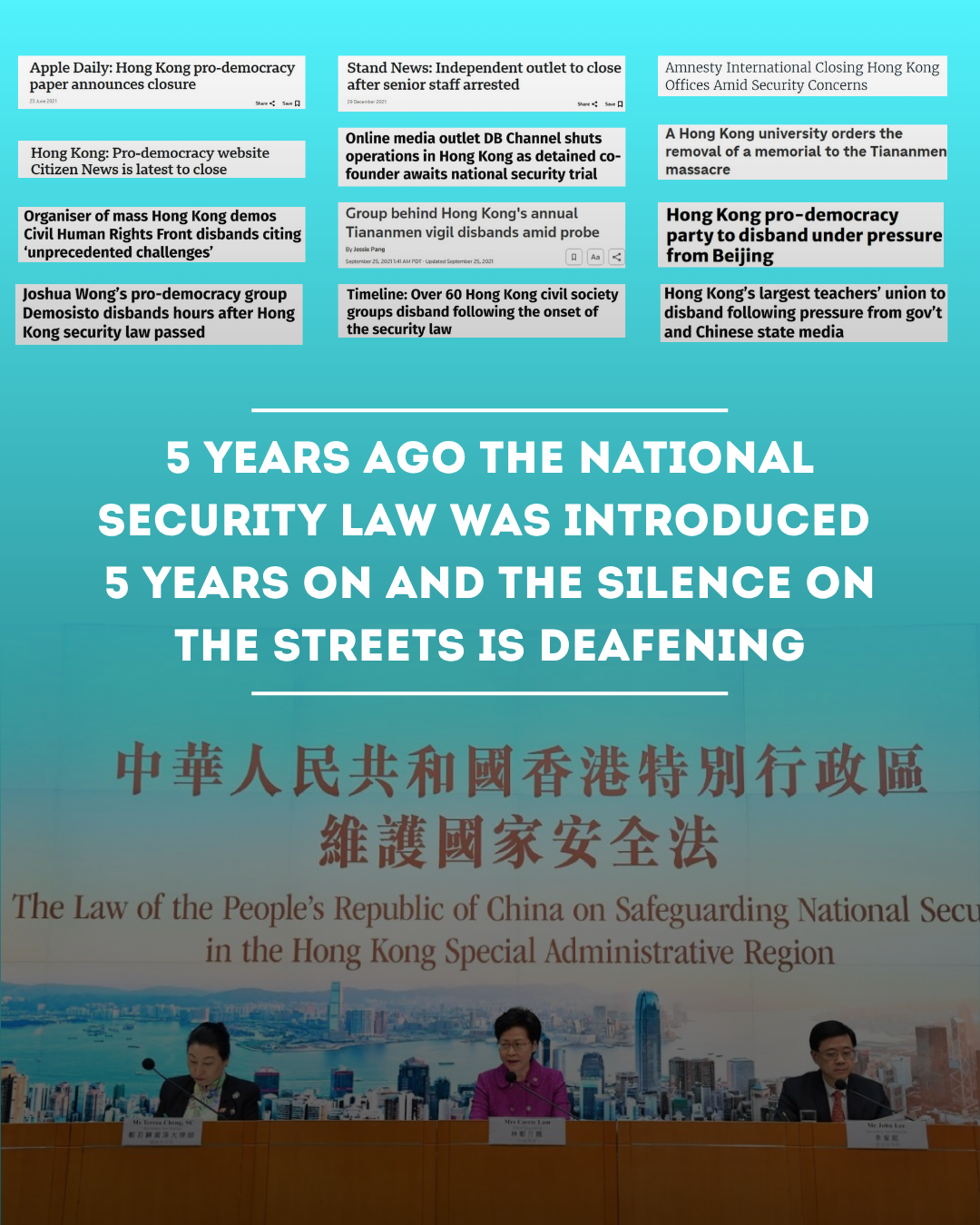

This censorship extends beyond Tiananmen to other pro-democracy movements. In Hong Kong, the 2020 National Security Law (NSL) effectively ended the city’s tradition of annual Tiananmen vigils, which had drawn tens of thousands to Victoria Park for decades. The Hong Kong Alliance, which organized these events, was forced to disband in 2021, and its June 4 Museum was shuttered. Leaders like Lee Cheuk-yan, Albert Ho, and Chow Hang-tung face trials for “inciting subversion,” with some scheduled for November 2025. Even minor acts of remembrance, such as lighting candles or wearing pro-democracy T-shirts, can lead to arrests under the NSL. In mainland China, activists like Chen Yunfei, a 1989 protest participant, and Yin Xu’an have been imprisoned for commemorating Tiananmen online or in public.

The continued imprisonment of Jimmy Lai represents the stark reality of this continuing crackdown. His imprisonment due to his pro-democracy activism and his role as a critic of the Chinese government, including his involvement in the 2019 pro-democracy protests and his alleged collusion with foreign forces and subsequent convicted on multiple charges, including fraud, sedition, and organising and participating in unlawful assemblies as well as additional charges under the national security law, his show trial and political imprisonment However, despite the actions of Caoilfhionn Gallagher KC to lead the #FreeJimmyLai campaign after 1,624 days in prison (as of 12th June) and the advocacy efforts of the Committee for Freedom in Hong Kong (CFHK) Foundation, governments including his own, the UK Government, continue to stay silent. All of which is an insult to the legacy of the Tiananmen Square movement.

A Broader Pattern of Human Rights Abuses

The Tiananmen crackdown established a blueprint for the CCP’s handling of dissent, evident in its policies toward ethnic and religious minorities. In Xinjiang, an estimated 1–2 million Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims have been detained in “re-education” camps since 2017, subjected to forced labour, torture, forced sterilisation, and cultural erasure. A 2022 United Nations report labelled these actions potential crimes against humanity, yet China dismisses them as anti-terrorism measures. In Tibet, over 930,000 rural Tibetans have been forcibly urbanised by 2025, disrupting traditional lifestyles, while religious freedoms are curtailed through state control over monasteries and the appointment of religious leaders. In Inner Mongolia, cultural assimilation policies have targeted ethnic Mongolians, including restrictions on their language in schools.

These abuses reflect a broader strategy of assimilating minority groups into a Han-centric national identity, often through coercion. The CCP’s tactics—mass surveillance, arbitrary detention, and cultural suppression—echo the authoritarian resolve displayed during Tiananmen. The lack of accountability for the 1989 massacre has emboldened the Party to escalate these violations, confident that domestic control and global influence will shield it from consequences.

Economic Power as a Shield

Post-Tiananmen, the CCP pursued rapid economic growth to restore legitimacy, transforming China into a global powerhouse. From 4.11% of global GDP in 1989 to 19.24% today, China’s economic “miracle” has lifted millions out of poverty—per capita income has risen over 900%, and poverty rates have fallen to under 1% by 2015. This “prosperity”, however, has come at the cost of political freedoms, with the CCP enforcing a “social contract” that trades civil liberties for economic security in a revived version of Mao Zedong’s Common Prosperity policy of ‘common prosperity’.

The Party has leveraged this so-called economic success to deflect human rights criticism. At the UN, China showcases images of prosperity to counter reports of abuses in Xinjiang or Hong Kong, promoting a narrative of “happiness” and stability over individual rights. Its Belt and Road Initiative and other economic ventures have secured loyalty from developing nations, silencing critics, media, and opposition in international forums. This strategy has allowed the CCP to refine its authoritarian model, using wealth and influence to shield itself from accountability for Tiananmen and subsequent violations.

Global Responses: Outrage Without Impact

The international response to Tiananmen and its aftermath reveals a pattern of initial outrage followed by accommodation. In 1989, Western nations imposed sanctions, including arms embargoes, and the UN Sub-Commission on Human Rights passed a rare resolution criticising China. Yet, by the 1990s, economic interests took precedence. The U.S. supported China’s 2001 entry into the World Trade Organisation, prioritising trade over human rights—a decision that some argue emboldened the CCP’s repressive tactics. The assumption that economic integration would lead to political liberalisation proved false, as China instead tightened control under leaders like Xi Jinping.

Recent years have seen a tougher stance. The U.S. and EU have imposed targeted sanctions on officials linked to Xinjiang abuses, and the U.S. Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act aims to curb goods produced with forced labour. Eleven countries boycotted the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics in protest of China’s human rights record (Lithuania, the U.S., Australia, UK, Canada, Kosovo, Belgium, Estonia, Taiwan, Denmark, and India.)

However, these actions are inconsistent. Many nations, wary of economic retaliation, avoid direct confrontation. The UK’s Labour government, for instance, is strengthening ties with China despite documented abuses, prioritising economic ties over principles. At the UN, China’s influence—bolstered by alliances with other authoritarian states—has weakened multilateral efforts, with reports like the 2022 Xinjiang assessment dismissed as “illegal.”

Civil society and diaspora communities have stepped into the breach. In 2025, 77 events across 40 cities in 10 countries, organised by groups like the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, will commemorate Tiananmen’s 36th anniversary. Taiwan, the only Chinese society able to freely hold Tiananmen memorials, hosts public vigils and discussions, contrasting with the restrictions in mainland China and Hong Kong. NGOs like Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, CFHK Foundation, International Parliamentary Alliance on China, and others document abuses and support groups like the Tiananmen Mothers, while activists like Hong Kong’s Chow Hang-tung continue to resist despite imprisonment. These efforts keep Tiananmen’s legacy alive, but their impact is limited by China’s censorship and extraterritorial harassment.

Has the World Learned?

I argue that the world has not fully learned from China’s overreach. The failure to sustain pressure post-Tiananmen allowed the CCP to perfect its playbook: suppress dissent, control narratives, and use economic leverage to deflect criticism. The assumption that economic growth would liberalise China has been disproven, as the Party has instead entrenched its authoritarian model. While recent scrutiny of Xinjiang and Hong Kong reflects growing awareness, economic dependencies, and China’s global clout, often mute effective action. The CCP’s export of surveillance technology and its influence over global narratives—through forums like the UN—pose a growing threat to human rights standards worldwide.

The lack of accountability for Tiananmen—no official acknowledgment, no reparations, no justice for victims—has set a precedent for impunity in cases like Xinjiang and Hong Kong. By engaging with China economically and diplomatically without robust human rights conditions, many nations have indirectly enabled the CCP’s model, which prioritises state stability over individual freedoms. This approach has inspired other authoritarian regimes, weakening the global human rights framework.

Yet, there are glimmers of progress. Targeted sanctions, legislation like the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, and civil society’s resilience show a partial awakening. The Tiananmen Mothers’ persistent advocacy, the “Bridge Man” protest of 2022, and the 2022 “White Paper” demonstrations against COVID-19 lockdowns demonstrate that defiance endures, even in the face of overwhelming repression. These acts, coupled with global commemorations, keep Tiananmen’s call for freedom alive.

A Path Forward

Calls to hold China accountable for human rights abuses continue to go unanswered by the international community, which seems happier to put economic prosperity before the lives of innocent men and women murdered by this regime of evil. However, A unified front would be able to counter China’s ability to divide critics, if only the political will existed.

Amplifying the work of groups like the Tiananmen Mothers and Hong Kong Watch, CFHK Foundation and other activist groups; providing platforms, funding, and protection for their advocacy would strengthen their resolve and ability to create meaningful change. Further, reducing reliance on Chinese markets to enable tougher stances on abuses without fear of economic retaliation would strengthen our ability to combat espionage and extraterritorial repression, while bolstering the rule of law. This requires diversifying supply chains and trade partnerships. We must collectively continue to counter China’s censorship by documenting and publicising Tiananmen and related abuses, ensuring they remain part of global consciousness through education and media.

The Tiananmen Square Massacre remains a stark reminder of the costs of unchecked authoritarianism. The CCP’s ability to erase its memory, crush dissent in Hong Kong, and perpetrate crimes against humanity in Xinjiang and Tibet reflects a failure to hold it accountable early on. While civil society and some governments have shown resolve, economic dependencies and China’s global influence have muted effective responses. The world’s partial learning from Tiananmen’s lessons—evident in sanctions and growing awareness—must translate into sustained action. By prioritising human rights over short-term gains, supporting activists, and preserving historical memory, the international community can honour the victims of Tiananmen and prevent further erosion of global human rights standards. The resilience of those who continue to resist, from the Tiananmen Mothers to Hong Kong’s jailed democrats, offers hope but only if the world finally listens.