This blog is authored by Shannon Van Sant, Strategy and Public Affairs Advisor at the Committee for Freedom in Hong Kong Foundation.

My insights drew on my experience working as a journalist in China for 12 years, where I observed interviewees navigating authoritarian lines around religious freedom in diverse ways.

My stories included self-immolations by Tibetans in Qinghai Province, where I spoke with my former translator, Tenzin, about people he knew who had set themselves on fire in opposition to Chinese Communist Party discrimination.

At the time, thousands of students in Tenzin’s home city of Tongren were protesting what they said was cultural genocide at the hands of the People’s Republic of China.

I had travelled twice to the Tibetan plateau in Qinghai, where Tenzin said state propaganda was driving local villagers to forget their culture, history, and religion. “We are becoming less brave and less willing to tell the truth,” Tenzin said. The self-immolations were sparked by a mounting sense of despair.

I sometimes observed those within the CCP struggling to navigate government lines around religion. Many years ago, I interviewed a central government official who had converted to Christianity and was encouraging his colleagues to expand religious freedom in China. However, that’s not the direction the CCP chose. By the end of my time in China, in 2017, the space for religious freedom and expression was tightening. Under President Xi Jinping’s leadership, authorities began destroying scores of churches in Wenzhou, which had previously been a vibrant centre of Christianity in China.

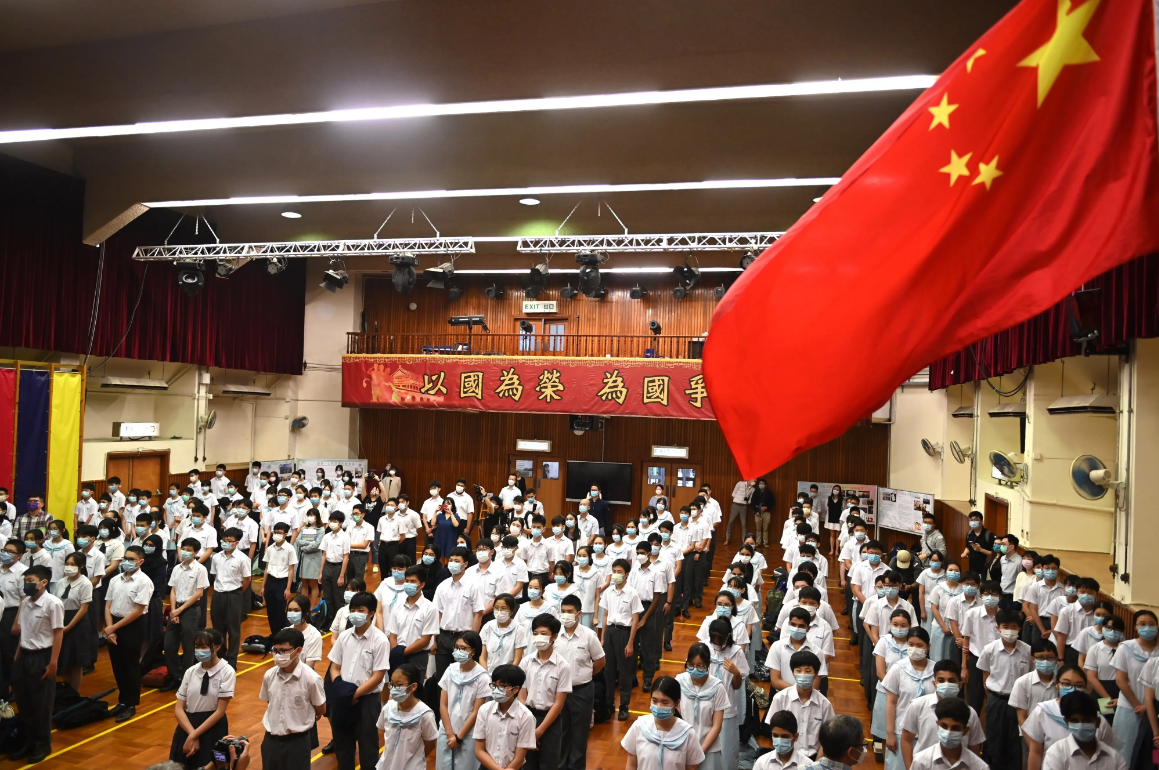

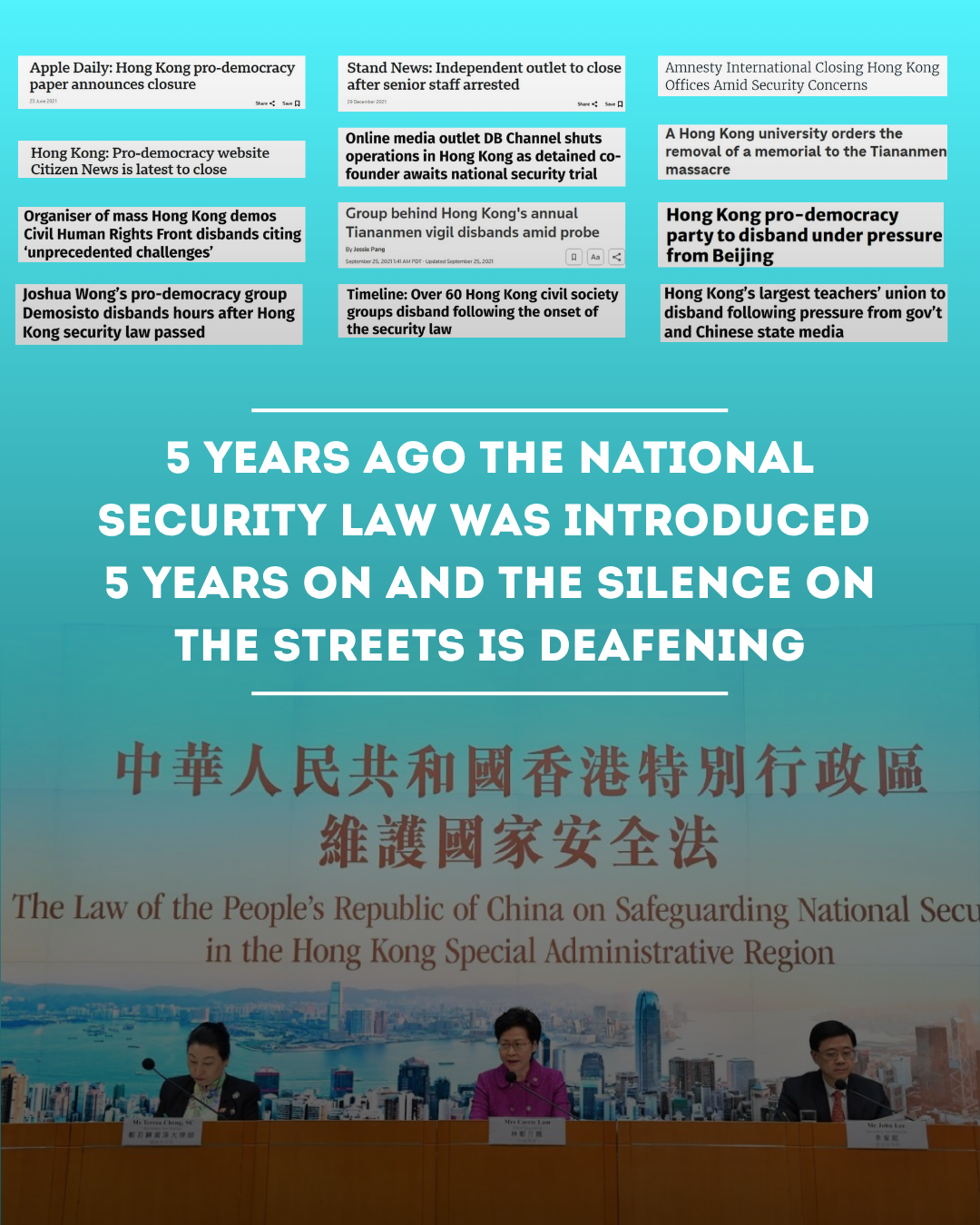

Now, the majority of my work focuses on Hong Kong. My colleague Frances Hui wrote an excellent report on the erosion of religious freedom in Hong Kong, which you can read here. While Hong Kongers can attend church, many sermons no longer mention the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, political or civic engagement in Hong Kong society, or human rights, for fear of angering the CCP. Similarly, some teachers at faith-based schools in Hong Kong no longer discuss these topics or stories of persecuted Christians with their students, to avoid angering authorities. Hui also writes about the co-optation and infiltration of Hong Kong churches by the CCP’s United Front Work Department, further stifling freedom of expression and speech.

At the Committee for Freedom in Hong Kong Foundation we seek to free political prisoners like democracy advocate Jimmy Lai, who converted to Catholicism in 1997. Lai has been refused communion in prison, and other political prisoners in Hong Kong have been denied religious materials.

To advance religious freedom around the world, I have a few recommendations. One common thread among my reporting experiences in China was accessibility. It’s hard in a country that succeeds in such control to hear people’s stories. You have to be intrepid, listen to people’s experiences, and tell them to the world. You must give these issues a platform, as I have tried to do. Whether you are a reporter, an NGO, non-profit, or policymaker, you should make religious freedom a priority and at the forefront of the issues you promote, talk about, and engage on.

Secondly, we should think creatively about reaching audiences that may be heavily influenced by state propaganda, to tell them stories of religious persecution, such as the use of forced labor in Xinjiang. I know that these audiences would be moved if they could hear and read such stories.

Most importantly, religion has provided Jimmy Lai and many of the Chinese human rights lawyers I had the fortune of meeting with a framework of values and the courage to stand up for their principles. We should elevate, illuminate, and embody these values, which are universal and include the promotion of human welfare and care for one another, whenever possible in our own advocacy and work.