This blog is authored by Darren Spinck, an associate research fellow for the Henry Jackson Society’s Centre for Indo-Pacific Studies.

The “Special Relationship” between the Trump White House and 10 Downing Street has already begun to show signs of strain. Incidents such as name-calling on both sides of the Atlantic and perceived tit-for-tat slights for official events—like the British Foreign Secretary initially hedging on a state visit for President Trump and the non-attendance of the UK Prime Minister at Trump’s inauguration—have worsened tensions. Additionally, reports suggest that the credentials for the Prime Minister’s appointment of the UK’s ambassador to the U.S., Peter Mandelson, may not be accepted.

However, amidst the ongoing drama surrounding U.S.-UK relations during Trump’s second presidency, Chancellor Rachel Reeve’s January visit to revive the UK-China Financial Dialogue could derail Washington-London ties even further.

The Chancellor met with CCP officials, hat in hand, seeking a “lifeline” for the UK’s flagging economy. Having already agreed to a “pared back” audit of UK relations with China, which had aimed to address the previous Government’s “inconsistent” China policy, the Chancellor flew back to London with investment commitments from China totalling a paltry £600 million through to 2030.

The Chinese, skilled negotiators as always, received assurances that PRC companies, facing risk of losing access to U.S. capital markets, would benefit from the UK-China Stock Connect program and “the promotion of Chinese companies jointly listed on the London Stock Exchange”. In addition, London and Beijing launched over-the-counter UK-China bond business and agreed to conduct a feasibility assessment on establishing exchange traded fund connect operations.

As the UK seemingly deepens its economic ties with the CCP and appears committed to strengthening the PRC’s access to western capital markers, London’s actions appear increasingly at odds with the stark warnings coming from its closest ally, the United States.

During his confirmation hearing, Secretary of State Marco Rubio stated, “we welcomed the Chinese Communist Party into this global order. And they took advantage of all its benefits. But they ignored all its obligations and responsibilities. Instead, they have lied, cheated, hacked, and stolen their way to global superpower status, at our expense”.

During a meeting before his Senate confirmation hearing, Secretary of the Treasury Scott Bessent called China’s economy “the most imbalanced, unbalanced… in the history of the world” and said U.S. investments have helped fuel China’s military modernisation. Despite Rubio’s and Bessent’s emphatic warnings about the dangers of continued economic interdependence with China, it seems the Starmer government seeks a return to the heady days of David Cameron’s “golden era” of UK-China relations.

As this author has recommended previously, the “UK and its closest trading partner [should] mitigate against further risks associated with trade dependencies on China and the CCP’s mercantilist-communist economic model.” The UK faces a £32.3 billion trade deficit with China (second-quarter 2024), while the U.S. lost 3.7 million manufacturing jobs from 2001-2018. There was a 20.3 percent decline in UK exports to China, in the year leading up to the second quarter of 2024, demonstrating China’s Dual Circulation economic model continues to favour one-sided trade and limit PRC reliance on foreign imports.

Vice President JD Vance has stated that the CCP built its middle class on the backs of American citizens, while the PRC’s approximately $10 billion investment into U.S. private and equity and venture firms over a decade span allowed the CCP to influence fund allocations and the behaviour of firms, according to the think tank American Compass.

Chancellor Reeves presented the CCP with a public relations victory with her visit to Shanghai, but she was not the only Starmer government official to do so. Separately, Energy Secretary Ed Miliband announced plans to visit China in 2025, potentially reviving the UK-China Energy Dialogue. Just prior to Trump’s November 2024 election, the Business and Trade Secretary, Jonathan Reynolds, stated the UK was “open” to restarting the UK-China Economic and Trade Commission. There are also plans to hold the 2nd UK-China Industrial Cooperation dialogue. As noted by Sam Goodman at the China Strategic Risks Institute, “this does lead to the question of why the current government believes it will be more successful in its engagement with China, gaining Chinese investment, and spurring UK economic growth than the previous governments of Brown, Cameron, May, and Johnson.”

Following President Trump’s January 20 inauguration, his White House and the Starmer government should put their personal and ideological differences aside and work toward common transatlantic security concerns vis-à-vis Beijing. A total and absolute decoupling of the transatlantic partners from China’s non-strategic sectors is likely not going to happen. However, London should work with the Trump administration’s efforts on key trade issues, including pressing Beijing to revalue its currency, reduce the trade deficit, and expand market access, which will help increase exports of U.S. and UK goods. Washington and London should also continue to tighten restrictions of Chinese investments into key sectors, and limit outbound investment and potential forced technology transfers into companies linked to the PRC’s Military-Civil Fusion sectors.

As the Trump administration focuses on securing transport corridors across the Western and Northern Hemispheres to prevent excessive CCP influence over supply chains and limit China’s ability to mobilise its military abroad, the Starmer government should also reconsider its ill-advised decision to transfer control of the Chagos Islands to Mauritius. Surrendering sovereignty over the Chagos Islands—which hosts the joint US-UK military base on Diego Garcia, including an American B-52 Stratofortress bomber squadron—would jeopardise critical strategic assets, especially given China’s significant leverage over Mauritius through trade and investment guarantees.

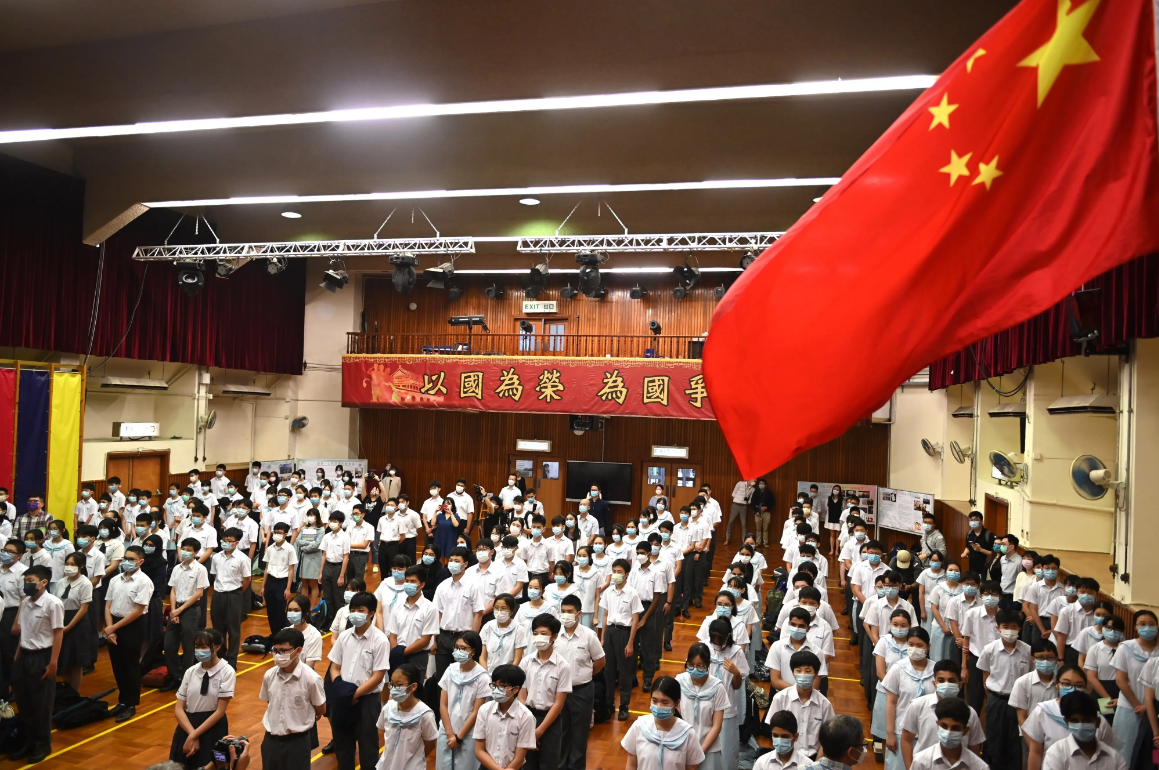

Finally, the UK has already acknowledged Beijing’s breach of international law by violating the legally binding Sino-British Joint Declaration and dismantling Hong Kong’s autonomy. While the Trump administration’s stance on sanctioning Hong Kong officials for democratisation and human rights concerns remains unclear, bipartisan support for such measures exists in the U.S. Congress. In a December 2023 letter to former Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, the co-chairs of the House Select Committee on the CCP wrote “the United States considers the Hong Kong National Security Law a brazen breach of China’s commitment to Hong Kong’s autonomy and democracy.” As Washington reviews its sanctions policy, including measures to present better defined terms for meeting benchmarks for lifting sanctions and to combat evasion, London should collaborate with Washington to prevent Hong Kong from further evolving into a hub for sanctions evasion.

By aligning shared transatlantic goals and prioritising long-term security over short-term economic gains, the UK can safeguard its sovereignty and economy and protect critical supply chains in the face of Beijing’s growing global influence.