This article is authored by Thomas E. Kellogg, Executive Director of the Center for Asian Law, where he oversees various programs related to law and governance in Asia. He is a leading scholar of legal reform in China, Chinese constitutionalism, and civil society movements in China.

Five years ago, at 23:00 on June 30, 2020, Hong Kong’s nearly quarter-century experiment in autonomy ended: the National Security Law (NSL) went into effect, fundamentally transforming the city’s constitutional structures and core institutions in ways that continue to resonate up to this day. Hong Kong is no longer autonomous. Instead, it is run by ultra-loyalist Hong Kong officials and hundreds of mainland officials who live and work in Hong Kong. And it is no longer free. A city once known for its boisterous and caustic political debate is now mostly quiet, and its leading politicians have traded in colorful Cantonese barbs for leaden Communist Party-speak slogans.

The NSL was enacted to transform Hong Kong, and it has succeeded. Numbers can tell part of the story: since the law went into effect, 332 people have been arrested, and 165 have been convicted and imprisoned, according to the Hong Kong government. At least 90 civil society organizations have been shuttered between July 2020 and March 2024, along with more than 20 media outlets, according to a recent report I co-authored with two Hong Konger colleagues. A more recent analysis found that over 250 workers’ unions have been deregistered over the past five years. An estimated 500,000 Hong Kongers have left the city over the past five years, many of them fleeing the repressive political environment. They have taken up residence in the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Taiwan, and elsewhere.

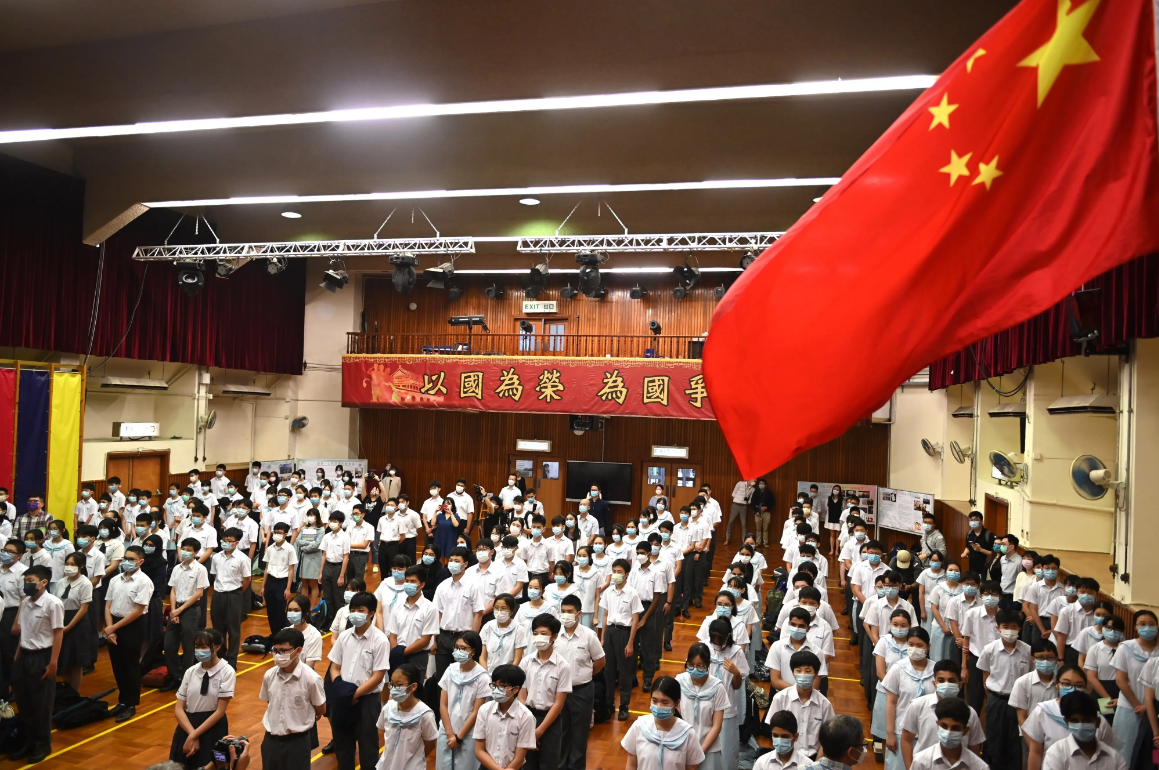

But many of the most far-reaching changes cannot be quantified: how to measure the quality-of-life decline that stems from the much-diminished arts scene? How to measure the impact, on Hong Kongers and visiting Mainlanders alike, as bookstores and publishers close, and books go unpublished, or even unwritten? What about the loss to public education as teachers who took part in pro-democracy protests are forced out of their schools, or resign rather than teach state-mandated national security content? All of these lower-profile changes have been a key part of Hong Kong’s transformation. They too, have changed everyday life for millions of Hong Kongers, even if they can’t easily be measured or quantified, or if they largely happen outside of public view.

Still, it makes sense to start with the NSL itself. After all, NSL criminal prosecutions targeting the leading lights of the pro-democracy movement have been the government’s primary tool of choice over the past five years. And it has been an effective one, from the government’s perspective: both the political impact and the human costs have been massive. Lives have been interrupted, families separated by prison bars, and careers derailed. Media mogul and pro-democracy advocate Jimmy Lai has been behind bars since December 2020 and faces a seemingly unending stream of criminal prosecutions that seem designed to keep him in prison for the rest of his days. Several dozen top pro-democratic lawmakers – the so-called Hong Kong 47 – have also been prosecuted, with 45 of the 47 sentenced to prison terms ranging from 4 to 10 years. Top journalists have been prosecuted under Hong Kong’s colonial-era sedition law, and several key media outlets have been forced to close.

These cases were the government’s top priority once the NSL went into effect. Just after the law was promulgated, several Hong Kongers told me privately that they expected that both Jimmy Lai and the pan-Democratic camp had national security targets on their backs. This prediction proved to be all too accurate.Jimmy Lai was arrested on August 10, 2020, making him one of the first high-profile NSL arrestees. Apple Daily’s offices were raided that same day. The Hong Kong 47 were arrested in a citywide operation on January 6, 2021, just over six months after the law went into effect.

But any assessment of the last five years would extend well beyond these and other more well-known cases. It would also cover dozens of other cases that generally haven’t made the news outside Hong Kong, and other moves by the Hong Kong government and Beijing as well. Let’s look at some of the key developments of the past five years and tease out what they mean for Hong Kong’s future.

Everyday Hong Kongers have been targeted. The list of national security targets is a who’s who of pro-democracy activism in Hong Kong, including leading lights like Joshua Wong and Agnes Chow. But the government has also used the NSL and the sedition provision of the Crimes Ordinance, now incorporated into the Safeguarding National Security Ordinance (SNSO), to arrest and imprison scores of anonymous Hong Kongers, whose only “crimes” include peacefully criticizing the government or publicly chanting pro-democracy protest slogans. Take the case of Chu Kai-pong, for example: Chu was arrested in June 2024 while wearing a t-shirt with the slogan, “Liberate Hong Kong, Revolution of Our Times.” Chu, 27 years old at the time of his arrest, later pled guilty to sedition, and was sentenced to 14 months in prison. His case is one of dozens in which Hong Kongers were prosecuted and imprisoned for engaging in peaceful political speech that should be protected under Hong Kong’s constitution, the Basic Law.

The courts have failed to protect basic rights. Chu Kai-pong’s case illustrates this basic fact: the courts have generally declined to apply constitutional human rights protections to national security cases. Instead, they have allowed the government to use the NSL and other laws to punish Hong Kongers for attempting to exercise their basic rights. Five years on, there is not a single case in which Basic Law human rights protections have played a meaningful role in shaping a court’s verdict.

This is not to say that the courts could have ignored the NSL after it went into effect. Without doubt, the courts have been put under extreme pressure by the Hong Kong government and Beijing. Both clearly expect the judiciary to deliver an unbroken stream of guilty verdicts in national security cases. For five years now, the courts have done exactly that, with precious few exceptions. While some judges are no doubt motivated to toe the line by a desire to curry favor with the government, others may well be trying to protect the court system from potentially serious backlash if the courts fail to deliver. In any case, the outcome remains the same: the courts have given the government a free hand to arrest and imprison virtually anyone it chooses. And the judiciary remains a passive and even marginal actor in this fundamental remaking of Hong Kong’s political and constitutional order.

Hong Kong’s national security state now stretches well beyond the NSL itself. The new regime includes new institutions created by the NSL, such as the powerful and secretive Office for Safeguarding National Security (OSNS). Also, several new laws have further expanded the government’s national security powers and further undermined basic rights. In March 2024, for example, the Legislative Council enacted the Safeguarding National Security Ordinance, which added several new national security crimes to Hong Kong law, while also dramatically expanding the government’s already broad national security powers. More recently, in May 2025, the government used its quasi-legislative authority to enact supplemental regulations that expanded the role of the Mainland-run Office for Safeguarding National Security, a clear violation of Hong Kong’s once-vaunted autonomy.

It’s unlikely that the government is done adding restrictive new laws to the books. Look for the Hong Kong government, and Beijing, to continue to push new laws through a pliant Legislative Council to address future political crises.

Beyond criminal prosecution, the government also uses extra-legal threats and harassment to keep its critics in line. Since July 2020, criminal prosecution under the NSL and the sedition provision of the SNSO have been the Hong Kong government’s primary tools for enforcing political red lines. But it also regularly relies on threats and intimidation to silence critics. In the spring of 2021, for example, the pro-Beijing Ta Kung Pao newspaper published an attack on the pro-democracy NGO Civil Human Rights Front (CHRF), calling it “the anti-China agent of chaos in Hong Kong.” This rhetorical strike, along with other moves, led to the closure of CHRF just months later. In other cases, the government has relied on threats of arrest and prosecution made to individuals behind closed doors, which similarly led several organizations to “voluntarily” shut down.

More recently, the government has used tax investigations and regulatory enforcement as its chief tool. The goal is not to force the closure of targeted groups, but rather to sap their resources and remind them that they could be shut down at any time. In May 2025, for example, the Hong Kong Journalists Association (HKJA) announced that it was being investigated by the Inland Revenue Department, along with six media outlets and several individual journalists. Selina Cheng, the chair of the HKJA, said that most of the tax investigations were launched without a sufficient evidentiary basis, raising concerns that the government was using the tax authority as a means to harass media outlets and journalists.

Hong Kong’s pan-democratic political parties have been decimated. One quick test of a political system’s level of openness is whether it permits opposition political parties, and whether these parties can run for election and win. For decades, Hong Kong – mostly, at least – passed this test. Members of Hong Kong’s pan-democratic opposition parties could run for seats in Hong Kong’s Legislative Council, and could run for District Council seats as well. They couldn’t run for Chief Executive, at least not in any meaningful way.

That changed after the NSL went into effect. Dozens of Hong Kong’s leading peaceful opposition figures were imprisoned, and the top pan-democratic political parties were harassed out of existence. The Civic Party was forced to close in May 2023. The Democratic Party held out for another two years, finally announcing its closure in April 2025. As this piece was getting ready for publication, the League of Social Democrats announced that it, too, was giving up and closing its doors.

It didn’t have to be this way: Hong Kong authorities could have allowed these parties to continue to operate, even in a much more constricted environment. It could have signaled an openness to dialogue with these groups, even as some of their top leaders went to prison. That less-bad outcome would have at least preserved these important parties as functional actors, so that they would be ready to ramp up their activities when the national security era ends. Instead, the government wanted them gone. This zero-tolerance approach speaks volumes as to the government’s vision for Hong Kong politics, both for now, and for years to come.

The business community faces increased risk. The business community has faced a number of challenges since the NSL went into effect. But for most of the past five years, businesses not run by pro-democracy advocates have generally not been targeted by the national security state. That may now be changing: many experts believe that the May 2025 SNSO supplemental regulations were issued as a direct rebuke – and a direct threat – to CK Hutchison, a leading Hong Kong company that had sought to sell its stake in two Panama Canal ports to the U.S. company BlackRock. Clearly displeased by the deal, Beijing reacted with rhetorical fury, republishing a Ta Kung Pao article that called the deal a “betrayal of all Chinese people.” Beijing almost certainly nudged the Hong Kong government to issue the new law, which opens the door to more direct involvement by the OSNS in national security cases, and imposes criminal penalties on those who fail to fully cooperate with OSNS investigations.

Under Article 55 of the NSL, the OSNS can take over a national security investigation, and transfer the case to the mainland for handling by legal authorities there. The subsidiary legislation was meant to operationalize Article 55, and served as a clear, and deeply worrying, signal that Article 55 could be used on a more regular basis in the months and years to come.

The implicit threat to Hutchison is clear: stop the proposed Panama ports deal, at least as initially constituted, or else Hutchison executives could find themselves being investigated – or worse – by the powerful OSNS. Other Hong Kong-based businesses whose interests overlap with Beijing’s should take note: the national security state is now keeping an eye on them, too.

Arrests and prosecutions have slowed, but the national security era isn’t over. With many of the top pro-democracy targets now eliminated, the pace of arrests has slowed dramatically: over the past 12 months, there have been just over a dozen known arrests, most of them under the SNSO. That said, the national security era is far from over: the NSL and the SNSO remain in force and continue to directly influence virtually every aspect of Hong Kong civic life. Key issues go undiscussed: no one will dare call for democratic reform anytime soon, for example, when they know that doing so could lead to criminal prosecution. And Hong Kong’s civic scene remains barren: no new political parties will be formed, and no new human rights monitoring groups will appear.

For those who have been imprisoned under the NSL or the SNSO and then released, reentry into society can be a struggle. Many have faced diminished social and economic prospects, as would-be employers, worried about their own safety, shun those who have been convicted of national security crimes. If this trend continues, these people could become, in essence, non-persons, whose professional and social prospects are limited, and whose political rights remain deeply circumscribed.

Take, for example, the case of pro-democracy activist Jimmy Sham, who was released from prison in May 2025. In an impromptu interview after his release, Sham declined to answer several questions posed by reporters. He instead noted that he needed to determine “where the red lines are drawn.” Sham also bypassed a query about whether he had been warned by the national security police about being in touch with certain people. Instead, he noted that, “of course, there are concerns that some things can’t be said.”

Even those who were merely investigated and not charged face far-reaching repercussions, beyond the bounds of the criminal justice system itself: In a recent interview with the South China Morning Post, former District Councillor Katrina Chan said that she had lost several jobs since her arrest. “I feel stuck,” she told the paper. “It’s difficult for me to plan anything for the future.”

At the same time, the unending national security era brings with it several downsides for the Hong Kong government and Beijing. The Hong Kong government continues to enforce strict speech and ideological red lines, even when doing so makes it look overly harsh and faintly ridiculous. It still seeks to use the law to threaten and harass overseas activists, which in turn creates friction between the Hong Kong government and its foreign counterparts. And the recent move to use national security laws to threaten CK Hutchison will likely do further damage to Hong Kong’s reputation as a key Asian business hub.

Looking back at the past five years, one can see clearly all that has been lost: a once vibrant and open society is now a shadow of its former self. Scores of individuals have been unjustly imprisoned, and many more have been arrested and investigated, even though they have committed no crime. Thousands have lost jobs or organizational homes, and hundreds of thousands have been forced into exile. It is a bleak picture, one that is unlikely to change anytime soon.

What will the next five years bring? If the Hong Kong government were wise, it would look at this ugly and shameful record and begin to change course. It could stop using the NSL and the SNSO to arrest people, for example, and drop ongoing cases that have yet to be concluded. It could allow all of the dissolved political parties, including the Democratic Party and the Civic Party, to reform, and it could repeal the far-reaching, anti-democratic changes to Hong Kong’s electoral system that were enacted in 2021. It could, with Beijing’s approval, bring the national security era to an end. The fact that such a scenario is unlikely in the near term doesn’t make it any less desirable, or potentially beneficial to the people of Hong Kong. It’s politically unimaginable, but it’s clearly the right thing to do.

Hong Kong’s national security era will eventually come to an end. It may have to wait until after Xi Jinping’s tenure as Communist Party Secretary finishes, which could come next year, or in three years, or five or 10 years from now. As with the passing of Chairman Mao, Xi’s passing from the scene will likely trigger a reassessment within the Party of China’s stagnant politics, its growing alignment with repressive regimes like Russia and Iran, and its grim, repressive future trajectory. That post-mortem could lead to a re-commitment to limited reform and openness, of course under the leadership of the Communist Party. If all of that happens – admittedly a number of ifs – then Hong Kong could stand to benefit. If all of that happens, Hong Kong’s autonomy could be restored, and One Country, Two Systems could be rebuilt.

In the meantime, those of us who care about Hong Kong will have to wait. We will continue to monitor political and legal developments in Hong Kong, and chronicle rights abuses. We will attempt to hold those who commit those abuses accountable, at least in the court of international public opinion. And we will hope that Hong Kongers themselves, both those now living overseas and those still in Hong Kong, will get their city back. After all, that beloved and beleaguered place belongs, first and foremost, to them.