This blog is authored by Michael Mo, a Former Hong Kong District Councillor and a Sanctuary Scholar at the University of Leeds’ School of Politics and International Studies. He is also the Co-founder and Director of the Hong Kong Scots.

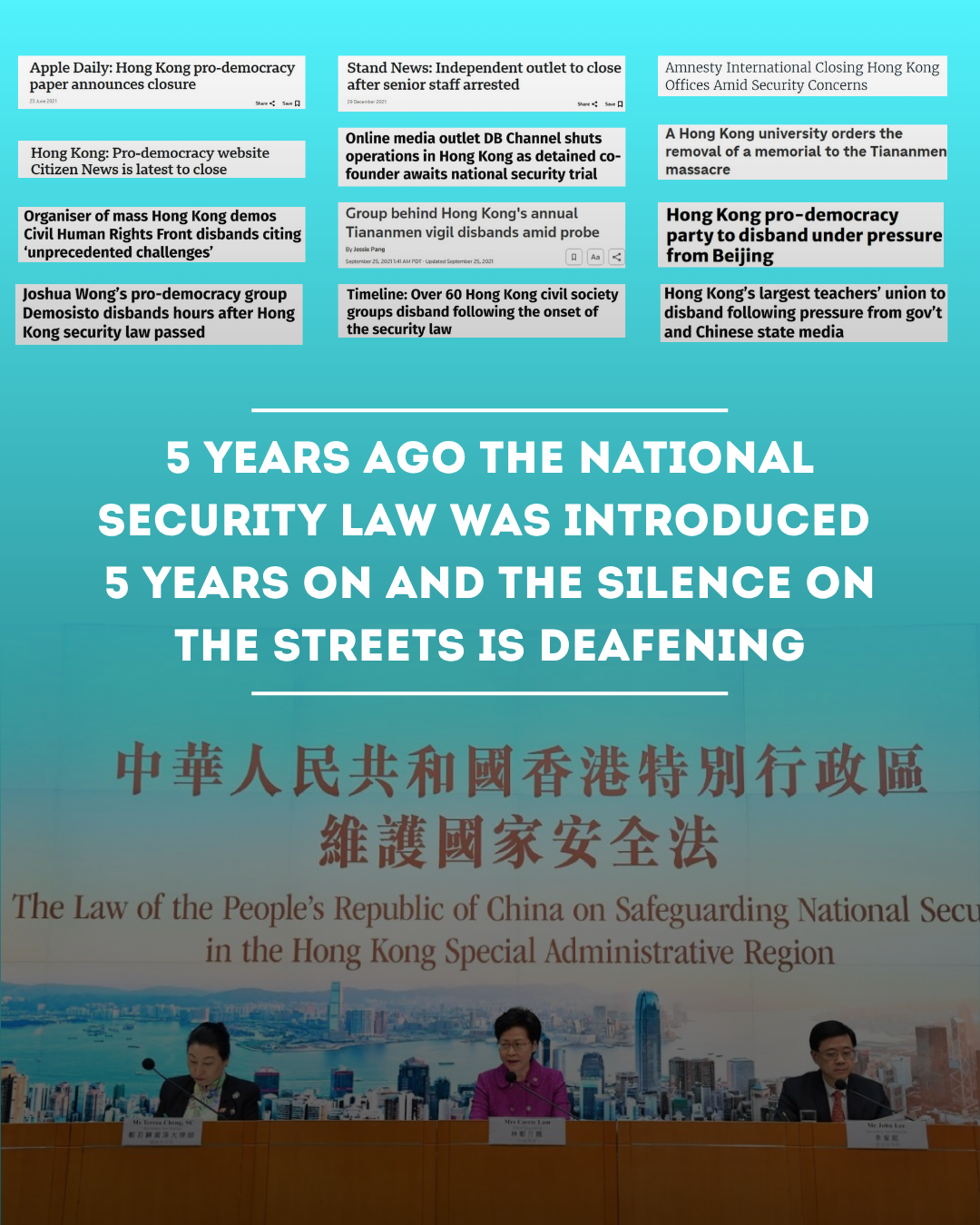

The lack of public backlash in 2024 is hardly surprising. Hong Kong authorities have thoroughly dismantled the city’s civil society, and dozens of Hong Kongers who make modest criticisms of the rigged electoral and political system have been jailed for sedition-related offences.

Hong Kongers fear even more for their safety as Article 23 looms. The proposed new security law may make it even easier for Hong Kong authorities to arrest and prosecute Hong Kongers who express their dissent, and courts could soon be instructed to hand down even harsher sentences than those under the current provision.

In the Article 23 consultation document, the Lee administration proposes broadening the current interpretation of “seditious intention” even further. For instance, the first proposed change criminalises anyone, wherever they are, if they are seen to have: “the intention to bring a Chinese citizen, Hong Kong permanent resident or a person in the HKSAR into hatred or contempt against, or to induce his disaffection against…the fundamental system of the State established by the Constitution…”. With China’s Constitution cementing the role of the ruling CCP in leading the country in a socialist system, anyone who advocates for a democratic, capitalist China and Hong Kong which is free from their rule can be considered a “seditious” criminal.

The plans also accuse anyone who has challenged “the constitutional order, executive, legislative or judicial authority of the HKSAR” as a criminal. In other words, anyone who advocates for abandoning the executive-led government or having a democratically elected attorney general is already committing a seditious crime.

While the consultation document suggested that people wishing to improve the system or constitutional order of China and Hong Kong authorities will not be considered to have “seditious intent”, the legal protection for such people is weak. Let’s imagine a hypothetical scenario in which a person might think Hong Kong can be improved if members of the Legislative Council were able to draft its Bills without prior approval from the Chief Executive, or who believes that the city should have a democratically elected attorney general. However, both propositions require amendment of the Basic Law, and the person who advocates for these beliefs cannot escape from suggesting the alteration of Hong Kong’s constitutional order. Also, the general public might become dissatisfied with the current constitutional order after hearing the idea or receiving leaflets about changing the Basic Law for good, leaving room for the national security police to interpret these views as seditious ones and thus worthy of arrest and prosecution.

The catch-all nature of the seditious intent in the new security is also a departure from the common law system. For instance, the recent case of Satnarayan Maharaj in the Privy Council of England recently ruled that the crime of seditious intention implies the intention to incite violence or disorder. While the case narrowed down the application of the law, the proposed legislation by the Hong Kong authorities remains the law to target pure speech and is likely to expand further its application to criminalise the promotion of a democratic China and Hong Kong by nonviolent means. The expansion also contravenes the recommendations made by the United Nations Human Rights Committee when they evaluated the city’s compliance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.